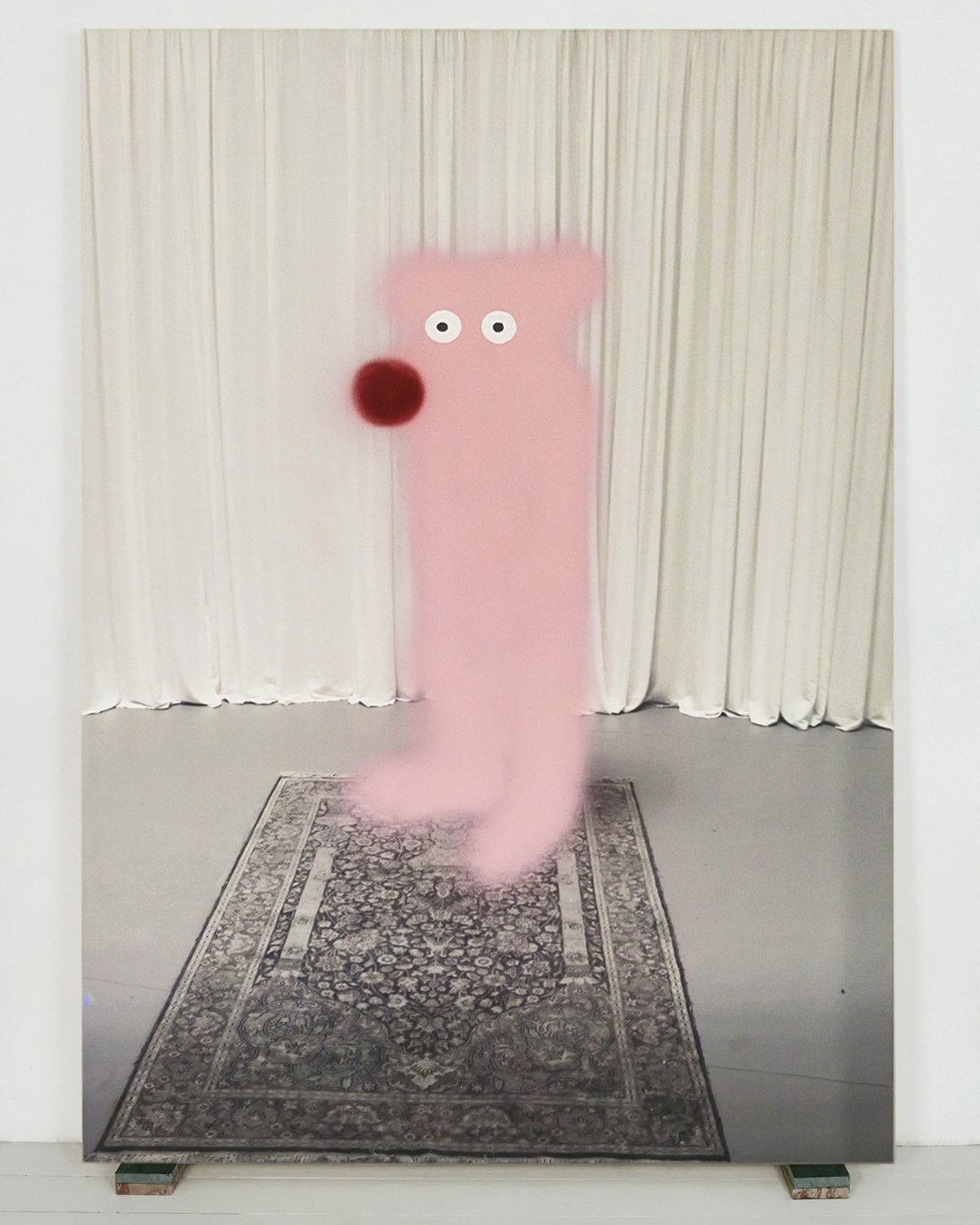

Teddy_MixMedia_204x140cm_2016

During my residency in Paris, amidst the city's inexhaustible cultural offerings, I visited the Louvre—a place I had long regarded as the pinnacle of artistic heritage. At that time, the museum was hosting Year One – Paradise on Earth, an exhibition by Italian artist Michelangelo Pistoletto, whose Third Paradise project optimistically envisioned the integration of humanity with nature and technology. While this utopian vision was intriguing, what fascinated me most was not the content of the exhibition itself but rather the spectacle of the Louvre as an institution and the way the global art system operates under the guise of universal inclusivity.

The Louvre, as one of the key sites of artistic power, shapes cultural narratives that define what is considered legitimate art. Although Pistoletto’s work formally spoke of harmony between humanity, nature, and technology, I couldn’t help but notice how this idealism was part of a larger system of artistic representation where the rules of the game were predetermined. Enormous queues, the ceaseless flow of visitors, the murmur of tour guides, and the omnipresent cameras created an atmosphere that felt more like an entertainment event than an encounter with art. The Louvre had transformed into a hyperreal space where the act of viewing became inseparable from the act of documenting—selfies in front of the Mona Lisa, fleeting glances, performative presence. In this environment, I encountered Pistoletto’s mirrored works, which allowed visitors to see their own reflections within the artwork. What was intended as an interactive installation was immediately absorbed into the endless cycle of digital self-representation, as visitors instinctively used the mirrors to capture themselves within the spectacle of the Louvre. I, too, participated in this ritual, creating a series of selfies that would later serve as the basis for Teddy.

This experience reminded me of Guy Debord and his critique of the society of the spectacle, prompting me to revisit the ideas of the Situationist International—one of the first structured critiques of imperialist art in the second half of the 20th century. Their method of détournement, radical artistic recontextualization, became central to my approach. Instead of merely referencing this theoretical platform, I wanted to enact its logic within my work—to manipulate the very tools of spectacle and consumerism that define contemporary cultural experience.

Teddy emerged as a détournement of my own presence in the Louvre. One of the selfie portraits, taken in the reflection of Pistoletto’s mirrors, was transformed into a digital print on canvas. However, the image did not remain intact—it was subjected to intervention, to disruption. I obscured the face with a cloud of pink mist using spray paint, forming the silhouette of a bear. This seemingly playful gesture—referencing carnival, disguise, and performative anonymity—serves as a critical commentary on both the act of self-representation and the function of the museum as a space of control and entertainment. The rough, street-inspired intervention stands in stark contrast to the institutional aesthetics of the museum. In this way, Teddy became something between documentation, reproduction, and subversion.

What also interested me was how an artist from the periphery, like myself, negotiates their position within such a system. Coming from the context of Serbia, a country in transition between socialist heritage and neoliberal capitalism, my artistic development has been in constant dialogue with the models dictated by global centers. In Belgrade, in spaces like BIGZ, art had a spontaneous and raw energy, far from spectacle and museum sterility. But the moment an artist attempts to cross the threshold of international visibility, they encounter a system where norms are already established, and where peripheral art is often exoticized or instrumentalized according to the needs of the center.

The bear, as an animated presence, becomes a paradoxical figure: both performer and observer, attraction and intruder. Drawing from animism, it symbolizes a state of awakening—a being caught between predator and prey, between spectacle and critique. In this sense, Teddy encapsulates the contradictions of the global art world itself. It reflects the entanglement of consumption and creation, between cultural participation and passive audience. This work not only critiques these conditions but absorbs them, using their mechanisms to expose them.

Reflecting again on Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q., I realized that Teddy is not a direct act of desecration but rather a playful yet urgent gesture—one that questions the conditions under which we experience art today. The bear’s bewildered expression, its quiet presence amidst the spectacle, mirrors the unresolved tensions of contemporary artistic production. It stands on the threshold between submission and agency, entertainment and subversion, quietly echoing Duchamp’s words: The artist must go underground.

This gesture not only problematizes the role of art in neoliberal capitalism but also raises broader questions about the colonial relationships between global centers and their peripheries. How can artists from countries like Serbia operate within a system that simultaneously includes and marginalizes them? How can subversion be enacted in a world where every critique is easily assimilated into its own aestheticized commodity form? Teddy does not offer direct answers, but it poses essential questions about the position of art in a world where the boundaries between freedom and manipulation are increasingly fluid.