Soma_FLUGallery_2016

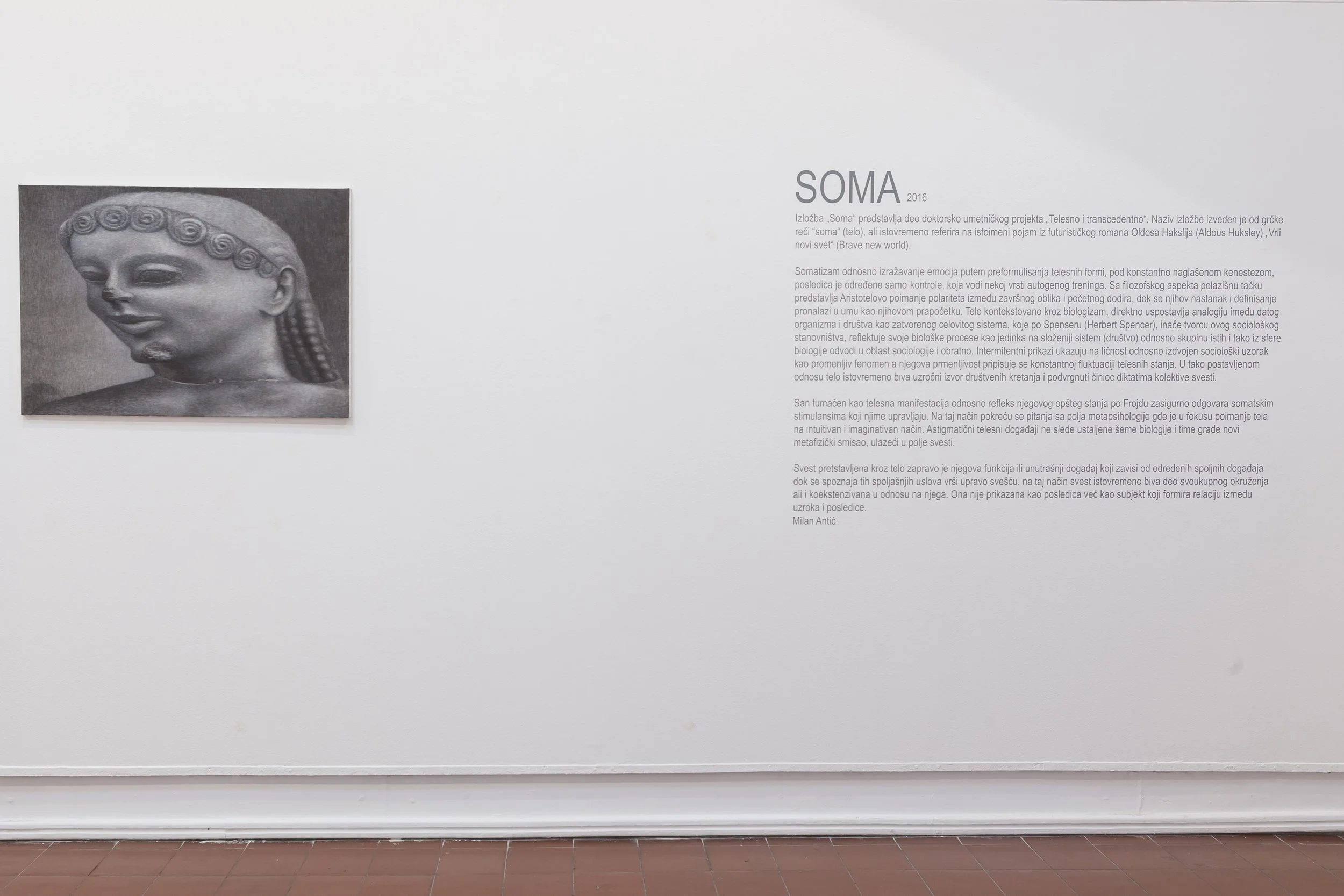

In SOMA, my 2016 solo exhibition at FLU Gallery in Belgrade, I explored the body as a space of tension, transformation, and contradiction. The title SOMA carries dual meanings—rooted in the Greek word for "body" while also referencing Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, where soma becomes a means of control, numbing society into submission. This layered reference reflects the way I approached the body in my work—not as a fixed entity, but as a site of negotiation between autonomy and regulation, identity and dissolution, biology and abstraction. For me, the body has always been more than a physical form; it is a vessel of memory, an emotional register, and a political surface. In SOMA, figures emerge and disappear, oscillating between clarity and dissolution, as if caught between states of being. In some works, I depicted young boys in delicate watercolor renderings, their faces marked by a sense of introspection and uncertainty. These fragile, almost ephemeral forms contrast sharply with other images in the exhibition—like the clenched fist, an isolated gesture that carries a multitude of meanings: resistance, tension, defiance, or control. Nearby, fragmented bodies of antique sculptures appear in shifting postures—some standing in dignified classical stances, others leaning, twisting, or broken, as if struggling against an invisible force. These sculptural references functioned as a bridge between historical representations of the body and contemporary perceptions of its fragility and resilience.

The contrast between these images was intentional. The soft washes of color in the watercolor portraits evoke a sense of vulnerability, while the rigid, fragmented sculptural bodies suggest endurance—remnants of an idealized past that have been fractured over time. The clenched hand, placed somewhere in between, serves as a liminal symbol, a point of tension between control and release. By juxtaposing these different approaches, I sought to question: What does it mean to inhabit a body today? How do we reconcile our physical reality with the weight of history, the constraints of society, and the emotions that shape our existence? A central thread in SOMA was somatization—the idea that emotional and social experiences manifest within the body. I was interested in how we physically carry emotions, how stress contorts posture, how trauma embeds itself in muscle memory, and how external pressures influence the way we move through the world.

When I created SOMA, the world was in the midst of political and social upheaval. The themes of bodily control and self-determination resonated with the events unfolding around me. Conversations about migration, surveillance, and bodily autonomy were at the forefront—global protests over identity rights, debates on the policing of bodies, and discussions about who controls the human form in political discourse. These ideas inevitably seeped into my work. The bodies in SOMA are not just individuals—they are bodies in negotiation with power, existing within systems that shape, define, and often confine them. Some stand with a defiant presence, while others appear fragmented, as if struggling to hold their form. The clenched fist, isolated in one of the paintings, carries a political charge—it is a symbol of resistance, but also of internalized struggle. Placed next to figures in classical sculptural poses, it questions the historical and cultural expectations imposed on the body—what it means to hold a stance, to present oneself in a way that signifies strength or submission. The young figures in the watercolors, in contrast, seem unburdened by this weight, yet their delicate renderings suggest an uncertainty about their place in the world. They exist in the liminal space between past and future, between innocence and responsibility. Their bodies, rendered with transparency and softness, contrast with the rigid depictions of the antique sculptures, yet both exist in a space of transition. The boys are in the process of becoming, their forms fluid and undefined, while the sculptures are frozen in time, their physicality altered by decay or intervention. This tension—between movement and stillness, between the organic and the artificial—echoes the way our bodies shift under the pressures of time, society, and memory.

When conceiving the exhibition space together with curator Miroslav Karic, we wanted the gallery to function as an extension of the body itself—a place where the viewer’s own physicality became part of the experience. The placement of the works encouraged movement: some pieces were hung high, forcing the viewer to look up, while others were placed low, requiring them to crouch. This was a deliberate strategy—an attempt to make the act of viewing a kinesthetic engagement, where the body was not just a passive observer but an active participant in the space. For me, SOMA remains a record of that time—both personally and politically. It is an exhibition about the fragility and resilience of the body, about how we negotiate our presence in the world, and about the ways in which art can act as an extension of the self. As I continue to explore these themes in my practice, I find that the questions posed in SOMA—about identity, control, and transformation—remain just as relevant today. Perhaps they always will be.