The Diary_Drawings_2007-2017

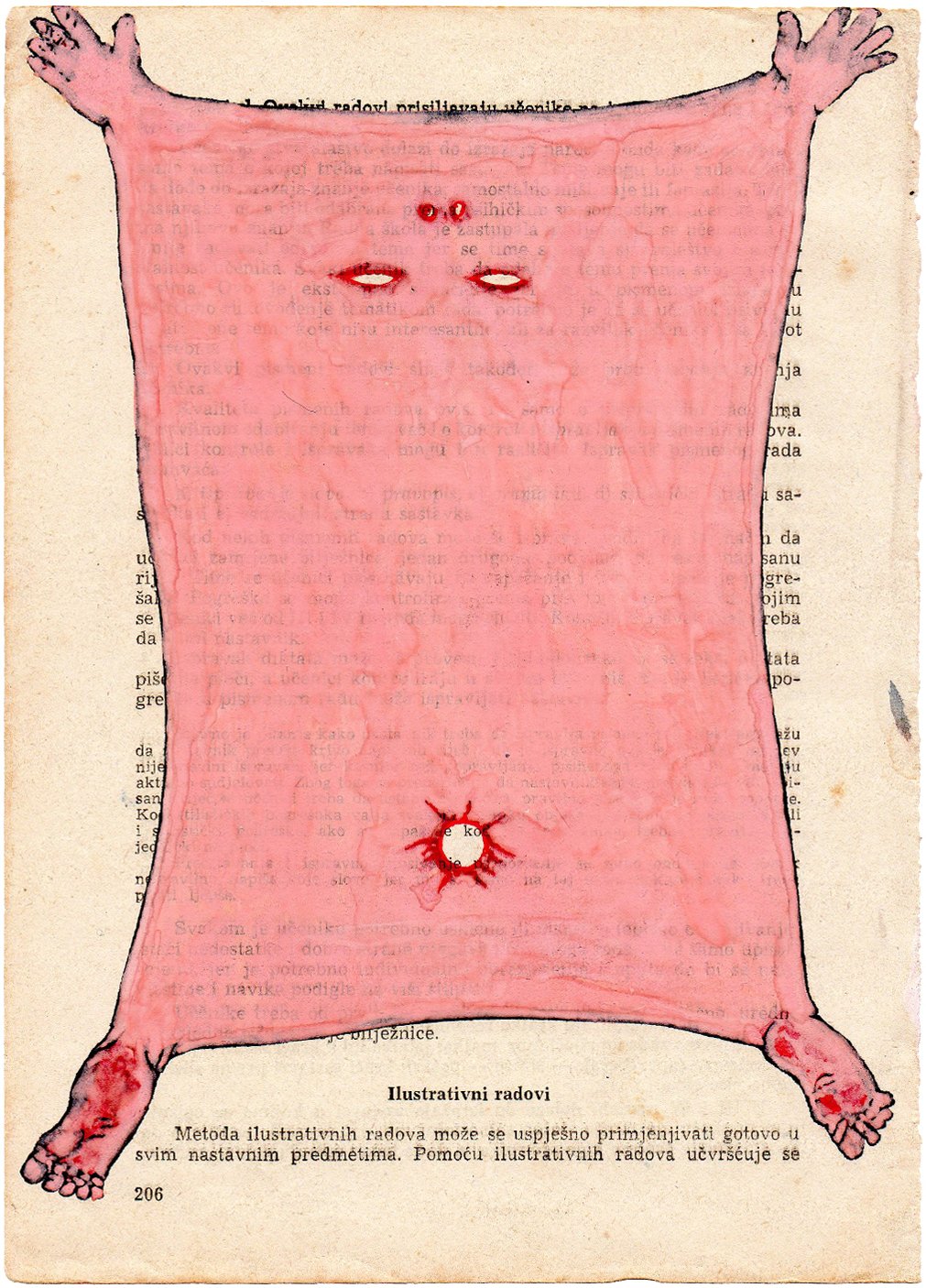

The first drawings in the Diary series emerged spontaneously while I was preparing for a pedagogy exam. Among the books available to me, I came across one that stood out—General Pedagogy, published in 1964 in Yugoslavia, which explored the socialist approach to education. Its content surprised me—overtly ideological texts depicted the socialist education system and its role in shaping societal subjects. Initially, I began sketching in the margins, but soon the drawings started to overflow onto the pages, turning into interventions that engaged in a dialogue with the text itself. They became spontaneous commentaries, graphic reactions to a discourse that felt distant yet simultaneously present in the educational structures I had passed through.

Over time, this process evolved into a long-term practice. For nearly a decade, I drew on the pages of found books, gradually obscuring the texts beneath layers of drawings, transforming them into visual archives where ideological, historical, and personal narratives intertwined.

What I gradually realized was that Diary does not merely document my personal process; it reflects a broader cultural transition—the shift from a socialist educational system to a world inundated with Western visual culture. I grew up in an environment where the socialist value system still had institutional strongholds, yet at the same time, new symbols entered my visual landscape—the energy of the streets, pop aesthetics, comic book culture, and the artistic language that dominated the late 20th century.

The visual expression of these drawings embodies this fusion of influences. There are clear references to the works of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, artists who redefined visual language in the 1980s, as well as to the Italian Transavantgarde, which viewed historical artistic motifs through the lens of postmodern appropriation. Additionally, subcultural aesthetics were equally important to me—primarily the visual language of comic books and the iconography that developed in football stadiums. Stadium art, with its improvised banners, gestural drawings, and raw crowd energy, became an essential part of my expression, reflecting the need for collective visual communication outside the confines of art institutions.

As the series developed, I became increasingly aware that Diary was not merely a personal journal but also a visual testimony of a period of transition—a moment when two ideological systems, two cultures, and two ways of understanding the world coexisted, overlapped, and clashed. On these pages, text and drawings are in constant negotiation—words from socialist pedagogical manuals are erased, covered, but also persist as part of a layered visual record. This work documents not only my artistic evolution but also how historical contexts inscribe themselves into our everyday visual practices.

Ultimately, I see Diary as an artistic archive that captures not only my personal fascination with change but also a cultural moment in which growing up meant existing between two equally present worlds—the old and the new. Through these drawings, I do not merely record this encounter; I reshape it, establishing a new dialogue between what is written and what is drawn.